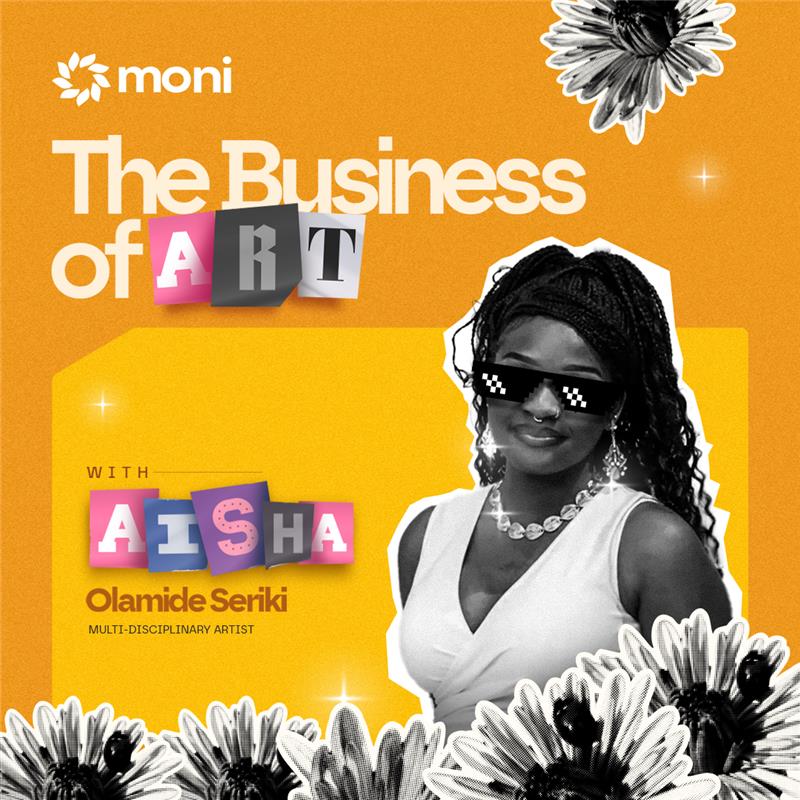

The Business of X: Moni is always on the lookout for groundbreaking business owners, creatives, and culture shapers who are building outside the box. The Business of X is a series of honest, behind-the-scenes conversations with people turning their passion into practice and unpacking how they make it work, what keeps them going, and the business lessons they’ve learned along the way.

Aisha Olamide Seriki’s work feels like memory made tangible. The multidisciplinary artist, whose practice spans photography, sculpture, and fine art, has developed a visual language rooted in care, spirit, and resistance. In this conversation, Aisha speaks with us about growing up in a photo-loving household, the spiritual roots of her practice, how she makes a living as an artist, and what it really means to create work that honours both the past and the future.

Q: Where were you born, where did you spend your childhood, and what was that experience like for you?

Aisha: I was born in Lagos and I spent the first five years of my life in India because of my dads job. After that, we returned to Lagos briefly and after a year, we left again for south east Asia. I remember that Malaysia, in particular, was one of my favourite places.

After all the constant travel, by the age of 8 my dad decided to move my family to the UK where the school system could support my development and I have lived here ever since.

Q: Was art something that was encouraged in your home growing up?

Aisha: I cannot remember a big presence of art outside photography during my early childhood years. My dad is an archivist by nature and loved photography. He documented everything about our childhood from minor to major limestones, events, himself and our travels. He has still kept this tradition until this present day.

When I moved to the UK, I developed an interest in art and eventually went on to take art for my GCSEs. During the course, I became drawn to photography and mixed media, primarily because of its power to bring stories to life. Photography for me at that moment was a way for me to express my narratives and perspective. That’s how it all began.

Q: Tell us about your art form. What drew you to it?

Aisha: I describe myself as a multidisciplinary artist. My work spans fine art, photography, and sculpture. I started thinking about images when I was around 16, and over time, my practice has evolved and matured. In the past two to three years, I feel like I’ve truly honed my voice.

One of the main themes in my work is exploring how history influences the present. My practice draws on both personal experiences and historical references. I aim to use these elements to navigate the world and challenge dominant perceptions—particularly those around Black bodies and identities.

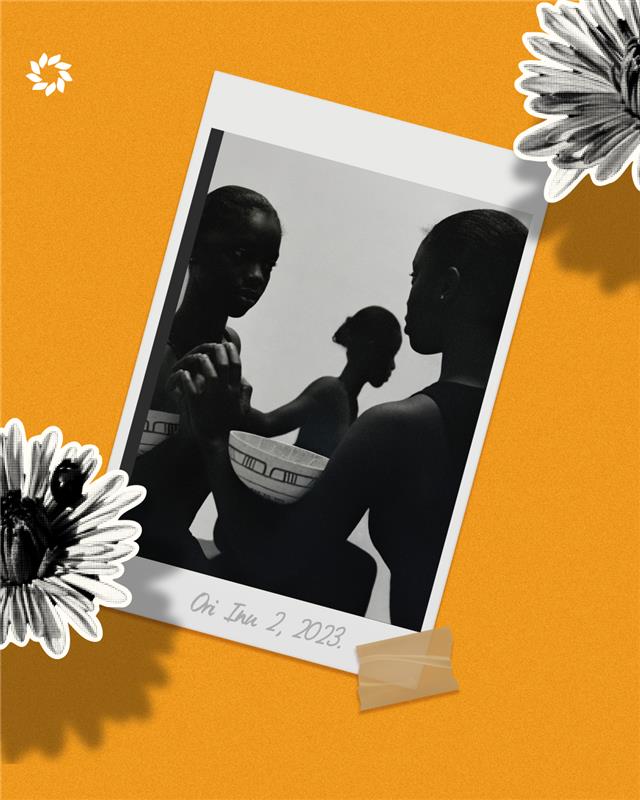

Photography plays a big role in that. I question how photography historic past, especially its role within colonization as a method for cataloguing and categorising marginalised people. I seek to challenge notion of the the photograph as an reliable source, and my practice analyses the link between photography and the truth as it relates to evidencing.For so long, it was commonly believed images were a reliable source of objectivity. ie what you see is what you get. With the rise of AI and advancement in retouching, it is now commonly accepted that images can be deceptive.

My work uses photography to create space for Black bodies to exist outside of these historic frameworks. I’m also deeply inspired by cosmology and spirituality, particularly Yoruba spirituality. It helps me challenge Western ideas about bodies and being. I’m really drawn to the concept of spirit and how it complicates the mind-body relationship. Including the spirit helps me explore parts of the self that are often ignored.

Sculpture is another aspect of my practice. I’m fascinated by symbols and how their meaning changes depending on personal experience. Domestic objects like combs and calabashes are recurring symbols in my work. I work with materials like wood and metal. Using these materials helps me understand embodiment—they require attention, care, and presence. So, working with my hands becomes another form of learning and expression.

Q: Do you have a day job, or other ways you support yourself alongside your art?

Aisha: Like many people, I’ve done a mix of things. Two years ago, I was let go from a job. At the time, it was really difficult, but I’m now grateful for it. I probably wouldn’t have left on my own to go freelance due to my fears of financial instability. As I was already doing my Master’s at the time, I took the dismissal as aa sign to focus on my practice and photography.

Since then, I’ve been fully freelance as a commercial photographer and an Artist. I do range of work spanning from portraits, jewellery photography and events. Initially when I started my commercial career, this came first before the art I wanted to be a fashion or portrait photographer. At the time it was frustrating getting jobs outside the realm of fashion and portraiture. However, as my art practice has begun to develop its own voice and identity, there is a boundary created from my paid commercial work and my artistic career. So I am more open to commercial work from different aspects of photography because it feels separate from my art career.

I also do some teaching and facilitation work, which I love. Art practice can be very self-centred—it’s about your own vision, your own work. Teaching allows me to extend those ideas into the community. It opens up conversations and gives me a chance to give back and learn from others too.

Sometimes, when money is tight or invoices are delayed—especially after traveling—I’ll pick up casual retail work. I used to feel bad about doing retail work, like I hadn’t progressed. However, at the nature of freelancing is that it is unstable. Money can be inconsistent—some months you’re great, others are dry. Then when the money does come in, you’re often using it to cover previous shortfalls. Working retail alongside my practice helps bridge that gap. It gives me stability when needed.

Q: Have you exhibited in any galleries or are there any you’d love to show your work in?

Yeah, I’ve had the pleasure of exhibiting. Last year was a really good year for me—I did over 10 shows, mostly group exhibitions, and one solo show. I’ve been lucky to have my work out there.

Right now, I think I have at least one exhibition per month. It’s been consistent like that, which is nice but also, surprisingly admin-heavy! I’m constantly going to pick up or drop off work, which is part of the job no one really talks about. One of my favourite moments last year was winning The V&A Parasol Foundation Prize for Women in Photography and doing my first solo show.

I’d love to do an exhibition in Nigeria next. That’s actually my next big goal, hopefully with my last project. Even if it’s just for a week, I’d love to show it at home.

We’d love to have you!

Thank you! I really hope it works out. I haven’t had a show in Nigeria yet, so it’s a milestone I’m working toward.

If you weren’t an artist, what would you be doing?

if I weren’t an artist, honestly, it might be nice to just have a job. I know that sounds odd, but sometimes when you’re on this side of things, structure sounds appealing. Of course, I know someone with that kind of stability might say the opposite!

But I think I’d probably have my own charity, working with young people—widening participation in the arts or just helping out however I can. Actually, scratch that, If I had a more traditional path, I think I’d be a lawyer. I would’ve studied law and probably focused on human rights. So either a lawyer or a founder of a youth-focused charity. Or both!

Q: Is there a stereotype or bias about female artists you’d like to raise?

Aisha: I think the biggest one is about sustainability; how are you going to make a living doing this? Thankfully, I haven’t had many external comments like that. I’m grateful I didn’t come from a family that questioned my career choice, but I know how discouraging it can be when that pressure comes from people close to you.

In my experience, I have found that there is still some work to be done in widening access for young poc and black photographers within the photography industry. Platforms like UK Black Female Photographers are doing amazing in educating and promoting opportunities for young black photographers. It does feel like things are slowly changing, especially with the strides that have been made by my peers, Latoya Okuneye, Delali Ayivi, Serena Brown, Shenell Kennedy, Satori Cascoe, and Ejatu Shaw to name a few.

Then there’s how photography is perceived in the art world. Some collectors don’t see the value of photography, or view it as fine art. Many galleries won’t even show photography, so the demand for photography is smaller within the wider art ecosystem, and right now, with the economic climate and inflation, people are less likely to take risks by showing and supporting emerging artists. This is challenging to navigate as a young artist, but I try to not let market pressures impact my work.

Aisha Seriki is carving out her own path, one that honours memory, spirit, and the everyday realities of making a living as an artist. Her story is a reminder that creative work doesn’t have to follow a single blueprint. It can be messy, intuitive, and still deeply meaningful.